Sunday, 23 May 2010

Belfast to Beirut : evasiveness of the past in post-war socities

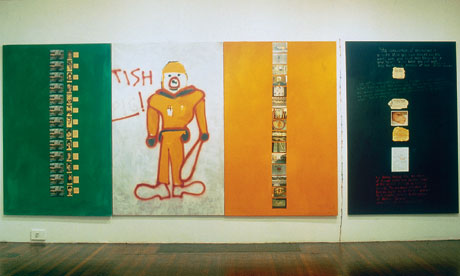

Furious ... Silver Liberties: A Souvenir of a Wonderful Anniversary Year, by Conrad Atkinson, 1978, on display at Wolverhampton art gallery. Photograph: Courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Art NYC

In 1978, staff at the Ulster Museum refused to display a work by the artist Conrad Atkinson called Silver Liberties: A Souvenir of a Wonderful Anniversary Year. This painting, embellished with barbed wire and newspaper cuttings, is a furious "souvenir" of Bloody Sunday. Three of its four panels are in the colours of the Irish flag; the fourth panel is black. Portraits of the 13 people killed that day, a graffito of a British soldier, street scenes in a Protestant part of Belfast and a beaten IRA suspect testify to the artist's rage. Protestant museum workers who saw it as a Republican banner of a painting won their argument and the work was censored. Today it forms part of the unique Troubles art collection at Wolverhampton art gallery, with a sea between it and Belfast.

Thirty-two years on, though, the incident has come back to haunt Britain's increasingly prestigious prize for museums. The Ulster museum is one of four on the shortlist for this year's Art Fund prize – the others are the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, Blists Hill Victorian Town at Ironbridge, and the Herbert in Coventry.

Belfast's revamped museum is surely a strong contender. Giving the prize to the other powerful candidate, the Ashmolean, would recognise excellence, but also confirm that excellence belongs in the elite citadels of southern English university towns. (Maybe that would be in line with our Etonian age.) Looking at photographs and reading reports – I have not yet had the chance to go there myself – the Ulster Museum has had a stylish, minimalist architectural makeover that makes it Belfast's "culture bunker", as people joke locally, according to the Irish Times.

But here's the rub. History clings. Conrad Atkinson is campaigning against the Ulster museum getting the award; and he is not its only critic. The Irish Times and others reviewed the museum's reopening last year with some scepticism. What had happened to the promised Troubles gallery that was going to hold up history for examination and debate?

The plan was to look frankly at Northern Ireland's recent past with shocking exhibits, including bloodstained clothes. Instead, the Troubles exhibit, say its critics, is small, muted and evasive. In particular, it does not have the gory display of real artefacts people expected, nor has it borrowed controversial works of art such as Silver Liberties – purchased for Wolverhampton, as it happens, by the very same Art Fund that offers this prize.

On the other hand, amnesia may be exactly what a society emerging from conflict needs. Historians of Ireland might point to a cultivation of memory as part of the problem, not the solution. Should forgetting be punished by the Art Fund prize – or rewarded?

0 Responses to “Belfast to Beirut : evasiveness of the past in post-war socities”

Post a Comment